This week’s blog is by Sharon Hudgins, and tells of a very memorable stay in a stone house in the Cairngorms, many years ago… As ever, if you also have a memorable story that you think might make a nice blog, please email it over to us! We love to publish contributions from others if we can.

I discovered the Cairngorm Reindeer Centre in 2017, while doing research for a book I’m writing about the Scottish Highlands. I should really say “re-discovered” the Reindeer Centre, because, to my surprise, research revealed that I’d actually been there once before, nearly half a century earlier.

In 1969, as a young American university student on my first trip abroad, I traveled by train around England and Scotland with my college roommate. Early in the trip, our route took us to Aviemore in the Cairngorms, because my roommate was an avid skier. We rode the ski lift up to the ski area, but that second week of May there was no snow suitable for skiing. It was just cold and sleeting on top of the mountain, cold and raining when we got back down to the bottom.

We needed to find a bed-and-breakfast where we could stay for the night and dry out our wet clothes. But it was already 6 p.m., and we had no idea where to go. That area wasn’t as developed for tourism as it is now. We finally found a tiny grocery store and asked the lady behind the counter if she knew a B&B where we might stay. She didn’t—but she asked the people standing in line, waiting to pay for their groceries, if any of them knew someone who could take us in for the night.

A man at the back of the line said we could stay at his place. We normally wouldn’t have accepted such an offer from a strange man. But we were soaking wet and didn’t seem to have any other options. Besides, everyone in the store seemed to know him, so it seemed like a pretty safe bet.

When we arrived at his grey stone house, we were surprised to find that his wife was an American. She seated us in front of the blazing fire in the sitting room, fed us a hot supper there, and chatted with us about our travels in Britain and our studies in the U.S., before fixing up two beds for us to sleep in that night.

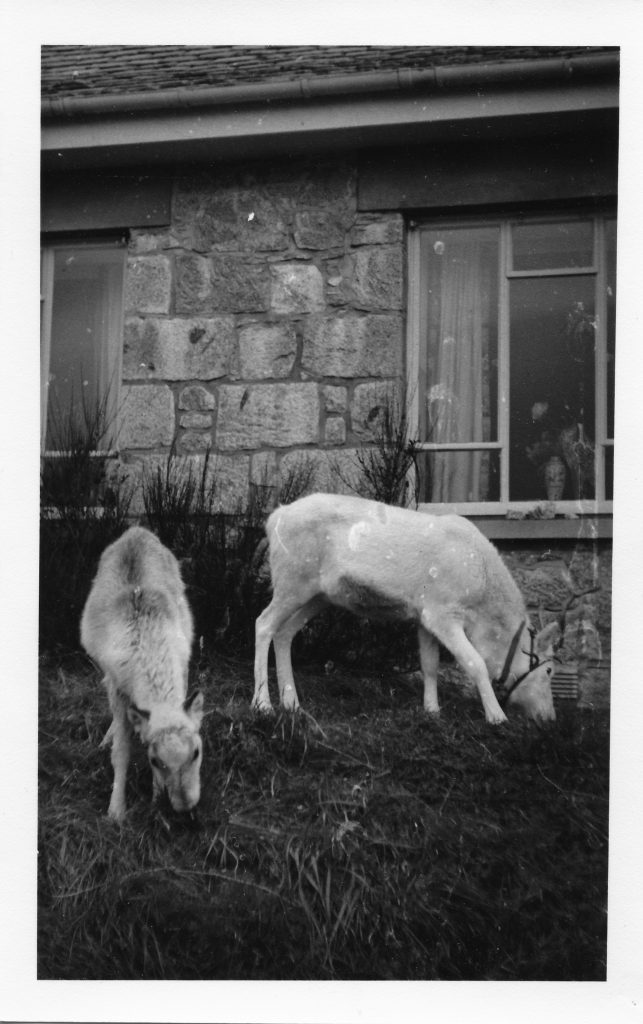

But the most memorable part of that chance encounter in the Cairngorms happened the next morning. After we’d eaten a hearty Scottish breakfast, the man took us out to the paddock behind the house to meet his reindeer—including a pure white reindeer which he said was the only white reindeer in Britain. I thought it was really cool to have reindeer in your backyard—especially a white one—and I never forgot that unusual experience.

Fast forward to 2017, when I was planning a journey around the Scottish Highlands to gather material for my book, retracing the exact route I had taken on that first trip in 1969. While researching “Aviemore” on the Internet, I came across a map showing the Cairngorm Reindeer Centre in that area. And I wondered if there was some connection with the reindeer owners I’d met there nearly 50 years before.

Through emails with Hen, one of the Centre’s herders, I discovered that the couple who had taken us in on that rainy night were Mikel Utsi, who had first introduced free-ranging reindeer to Scotland in 1952, and his wife Dr. Ethel Lindgren, who was also a reindeer expert.

I also learned that the white reindeer I had met in 1969 was named Snowflake, the first pure white reindeer born in the herd – and her distinctive white descendants are still part of the herd today.

When my husband and I visited the Reindeer Centre in the summer of 2017, I was delighted to see the same stone house where I’d once stayed overnight, with its reindeer paddock still out back. Although our travel schedule precluded a hike up into the hills to see the main herd, we did get to visit some of the reindeer kept inside the fencing behind the house. And I also stocked up on reindeer books and souvenirs in the Centre’s gift shop—which was originally the room where I’d dried out in front of the Utsi-Lindgren’s fireplace.

My husband and I are also happy to have become supporters of the Cairngorm Reindeer Centre by adopting two reindeer, LX and Mozzarella, direct descendants of that beautiful white Snowflake that I’d met so long ago, when she was only one year old. Whenever it’s safe to travel again, we look forward to visiting the herd up on the hills, meeting “our” two reindeer, and letting them know that once I’d even met their great-great-great-great-etc. grandmother, too.

Sharon Hudgins is an American author who has written books about Siberia and Spain. She is now working on a memoir about the Scottish Highlands. See www.sharonhudgins.com