A few months ago I wrote a blog about how we choose the names for the individual reindeer in the herd, and the themes we use each year. I mentioned, however, that there are always exceptions to the rule, so I thought I’d explain a few of the odder names in the herd, which don’t fit their theme. Most names do fit – even in a rather vague roundabout manner – but sometimes they just don’t at all!

First up, Hamish. Hamish was born in 2010, the product of his mother Rusa’s teenage pregnancy. Teenage in reindeer years that is, at 2 years old. Reindeer generally don’t have their first calf until 3 year olds, but some will calve as 2 year olds occasionally, especially if they are of decent body size already during the preceding rut, triggering them to come into season. Rusa was one such female, but unfortunately Hamish was also a large calf, and he got stuck being born. This resulted in a bit of assistance needed from us, and then a course of penicillin for Rusa, which interrupted her milk flow. We therefore bottle-fed Hamish for the first 2 or 3 weeks of his life, and any calf who we work so closely with at such a young age either requires naming, or ends up with a questionable nickname that sticks (a la Holy Moley!). In Hamish’s case we hadn’t already chosen the theme for the year, so just decided we’d choose a nice, strong Scottish name. And Hamish went on to grow into a nice, strong Scottish reindeer!

Svalbard next. While we’ve used both ‘Scottish islands’ and ‘foreign countries’ as themes, we haven’t technically done ‘foreign islands’. So where does his name come from? In fact, he was originally named Meccano, in the Games and Pastimes year. But at around 3 months old he was orphaned, and while he did obviously survive, it will have been a struggle, stealing milk from other females but never quite getting enough (this was while out free-ranging, so we weren’t around to help). As a result when we came across him a month or so later his growth had been stunted a bit, and he was very pot-bellied – a sign of inadequate nutrition.

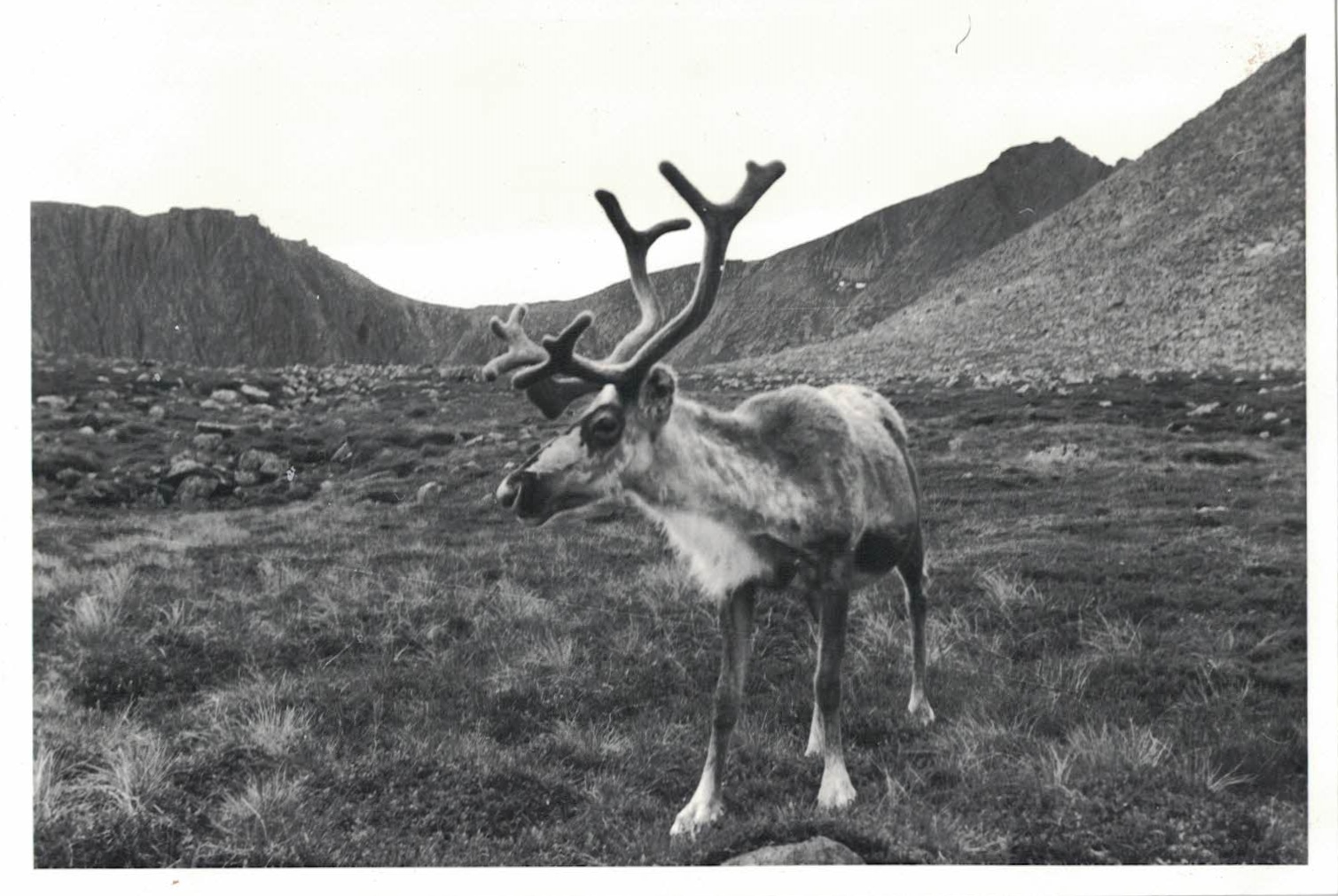

On the Norwegian-owned island of Svalbard there is a subspecies of reindeer (imaginatively called Svalbard reindeer). Without any need to migrate anywhere, over time Svalbard reindeer have evolved shorter legs and a dumpy appearance, and Meccano resembled a Svalbard calf. Never one to like diversion from a neat list of themed names, I tried in vain to call him Meccano but eventually gave up. ‘The Svalbard calf’ had become ‘Svalbard’. Oh well. It does suit him.

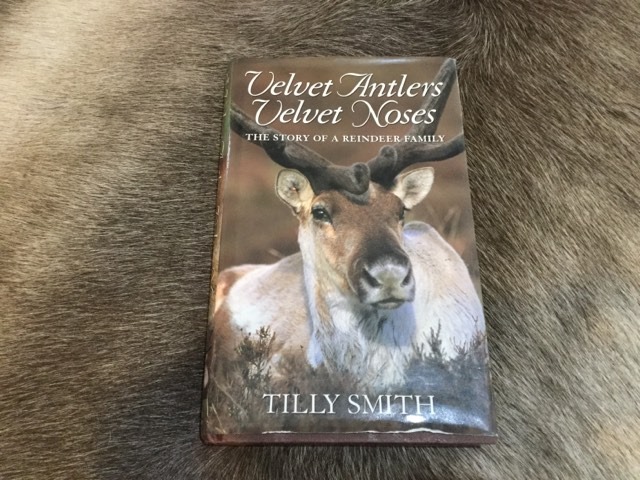

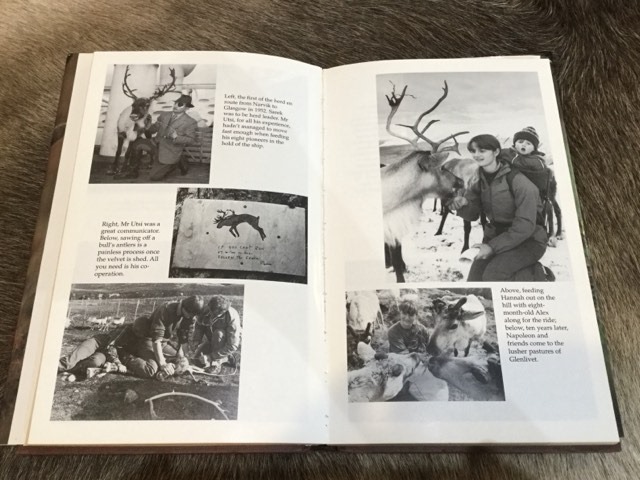

And then there’s Stenoa. He was born in 2012 when our theme was ‘Things that happened in 2012’ (being as quite a lot of things did that year – the Olympics, the Queen’s Jubilee and most importantly, our 60th anniversary). Most of that year of reindeer have names with rather tenuous links to the theme, but Stenoa’s is probably the most obscure. Taking part in the Thames flotilla for the Jubilee was the Smith Family onboard the boat Stenoa, which belonged to Tilly’s dad and was given her name from the first name initials of Tilly, her three siblings and parents.

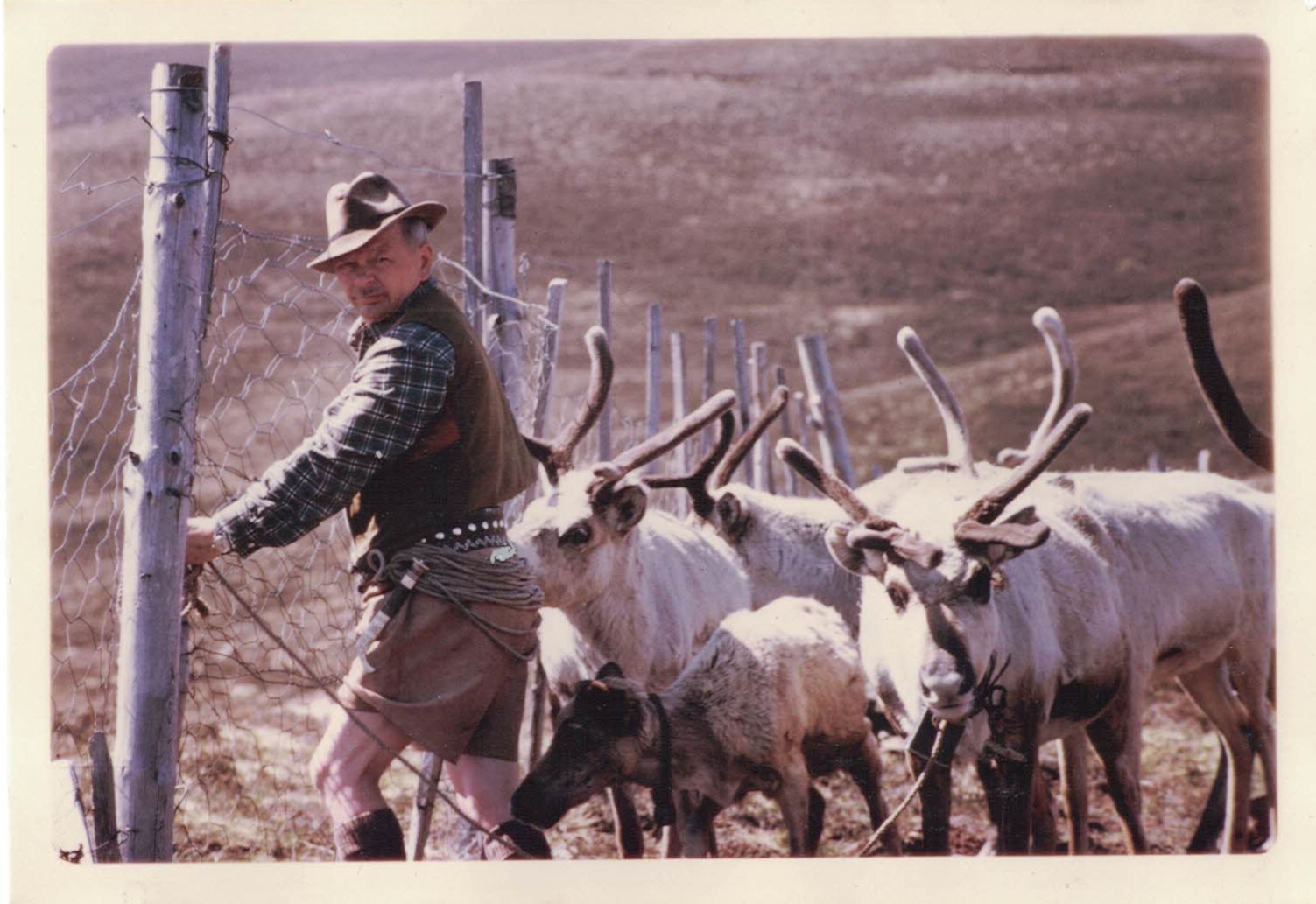

Every now and then we import some reindeer from Sweden, bringing them into our herd to bring in fresh bloodlines and to therefore reduce the risk of us inbreeding within the herd. There are currently about a dozen ‘Swedes’ in the herd, and while most have Swedish names, some don’t. In 2011, when they arrived to join our reindeer, we were all allowed to name one each, with Alex (out in Sweden with the reindeer while they were in quarantine), named the others – mostly after people they were bought from. So we have Bovril, Houdini and Spike still amongst the more traditional names… ‘My’ reindeer was named Gin (read into that what you will…) but sadly isn’t with us anymore.

Other than Holy Moley (explained in Fiona’s recent blog), the only calf who doesn’t quite fit last year’s Seeds, Peas and Beans’ theme is Juniper. On the day we named the class of 2020, Tilly’s long-time favourite (and ancient) Belted Galloway cow, Balcorrach Juniper, died, and her one request was that we name a calf in her honour. No point arguing with the boss! And juniper plants do have seeds I guess.

There’s been plenty more in the past (Paintpot for example, born with one black leg which looked like he’d stepped in a pot of paint) but I think that’s the main ones covered in today’s herd. But no doubt others will come along in time, and the cycle of constantly explaining a reindeer’s odd name to visitors on a Hill Trip will continue.

Hen