I’m from New Zealand so anything Southern Hemisphere-related reminds me of home..

I have been doing some research about any reindeer activity in the Southern Hemisphere. As we all know reindeer are native to the Arctic region but it appears they quite like the Antarctic region as well. Though animals introduced outside their native land always have some sort of impact.

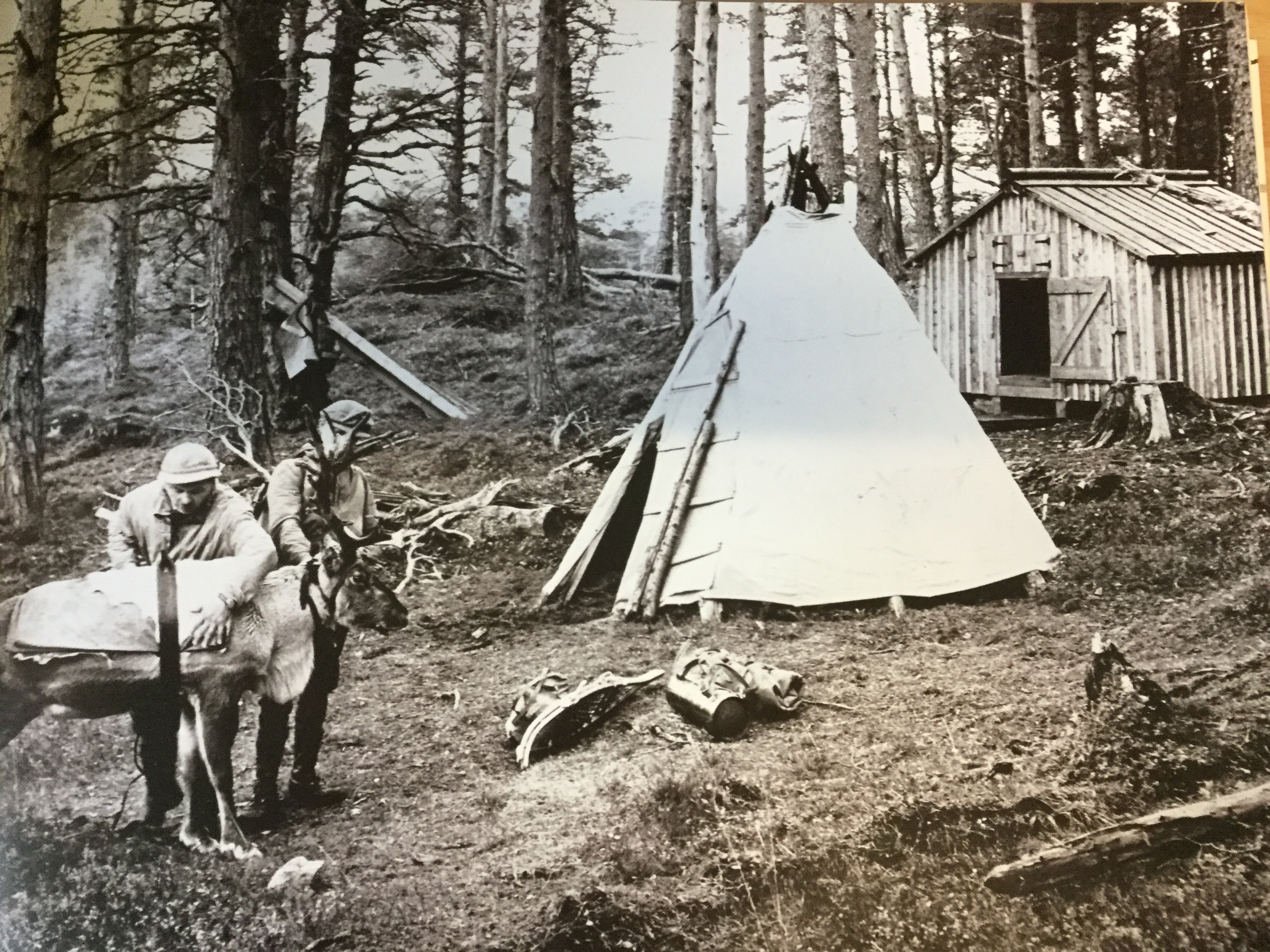

In 1911 Norwegian whalers introduced reindeer onto South Georgia. South Georgia is a sub-Antarctic island situated in the South Atlantic about 1000 miles off the western coast of Argentina. It is almost exactly the same distance from the equator as we are here in Scotland. It is a remote and inhospitable collection of islands and just what reindeer like!

The reindeer were introduced to provide recreational hunting and for fresh meat for the numerous people working in the whaling industry at the time. Since the end of the Whaling industry in 1960s the reindeer population had been growing uncontrollably. In 2011 it was noted that their numbers had exploded and the islands habitats were being destroyed. Fears of forcing some birds into extinction it was decided to eradicate the island of its reindeer population.

As these reindeer were introduced outside of their native range they were having significant impact on flora and fauna. Their range on the island was limited by natural glacial borders meaning their density increased to much higher than normal levels. In the Cairngorms we have a density of approximately one reindeer per square kilometre. On South Georgia the density had swollen to between 40 and 80 reindeer per km2. Imagine the northern corries here in the Cairngorms with 3000 – 6000 reindeer! The available land on South Georgia couldn’t support this many reindeer leaving many to die of starvation in the winter. Another common cause of death was falling from cliffs while trying to access ungrazed areas.

Over two years from 2013, 6,690 reindeer were culled on South Georgia. Animal welfare professionals were involved and 7500kg of meat was recovered.

In an attempt to diversify agriculture on the Falkland Islands around 50 reindeer were translocated from South Georgia prior to the eradication. I couldn’t find much information about this farming enterprise online but let’s hope it doesn’t end in another ecological nightmare!

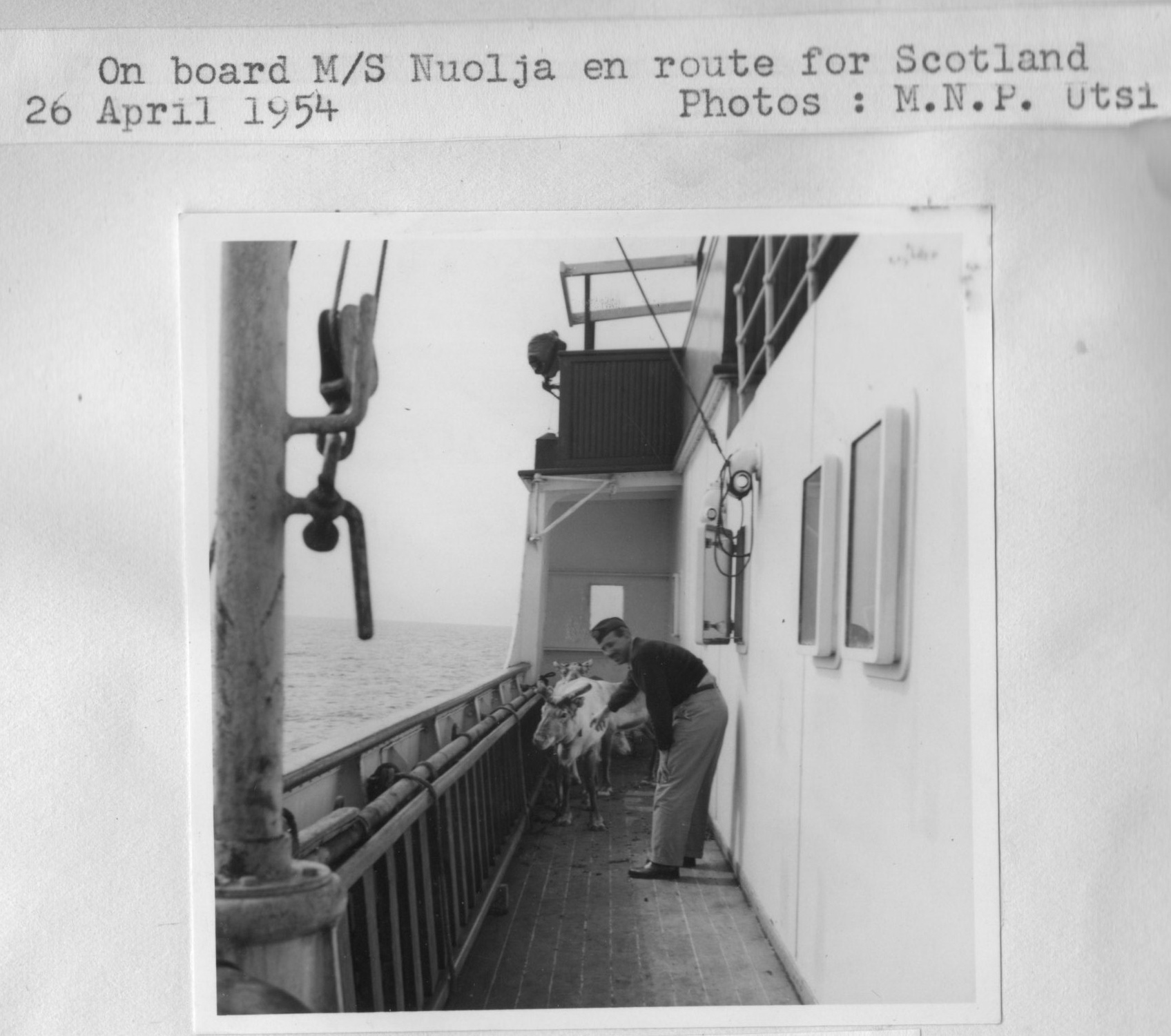

Reindeer were also introduced to the sub-Antarctic Kerguelen Islands in 1954 this time however from Swedish Lapland. The Kerguelen Islands are a French territory in the southern Indian Ocean. In the 1970s reindeer numbers were recorded at 2000. Unsuccessful attempts to introduce reindeer to Chile and Argentina also occurred in the 1940s.

So where does all this info leave us? It seems reindeer are extremely well suited for the sub Antarctic climate but without close and continued management is a very risky game as they are not native to the region. And for me, it seems I may be able to continue my career as a Reindeer Herder in the Southern Hemisphere, if I ever go back.

Dave